Community is Key: Invest in Health Outside Hospitals

8 October 2024 | Kirit Sehmbi

Too many people end up in hospital, because too little is spent in the community.

Lord DarziLord Darzi’s recent independent investigation into the state of the NHS report screams for a radical change in how we think about healthcare. We need to invest in healthcare outside of the clinic walls if we want a healthier society. Health promotion and education is the bread and butter of nursing. As a community nurse, this is something my colleagues and I have been asking for years as we see the cost of its loss through our day-to-day work.

Under-investing in the community healthcare workforce and services has led to staff burnout and acute care services being clogged up. The over-focus on hospitals and secondary care has also skewed our understanding of health towards more acute needs, which runs the risk of neglecting early intervention.

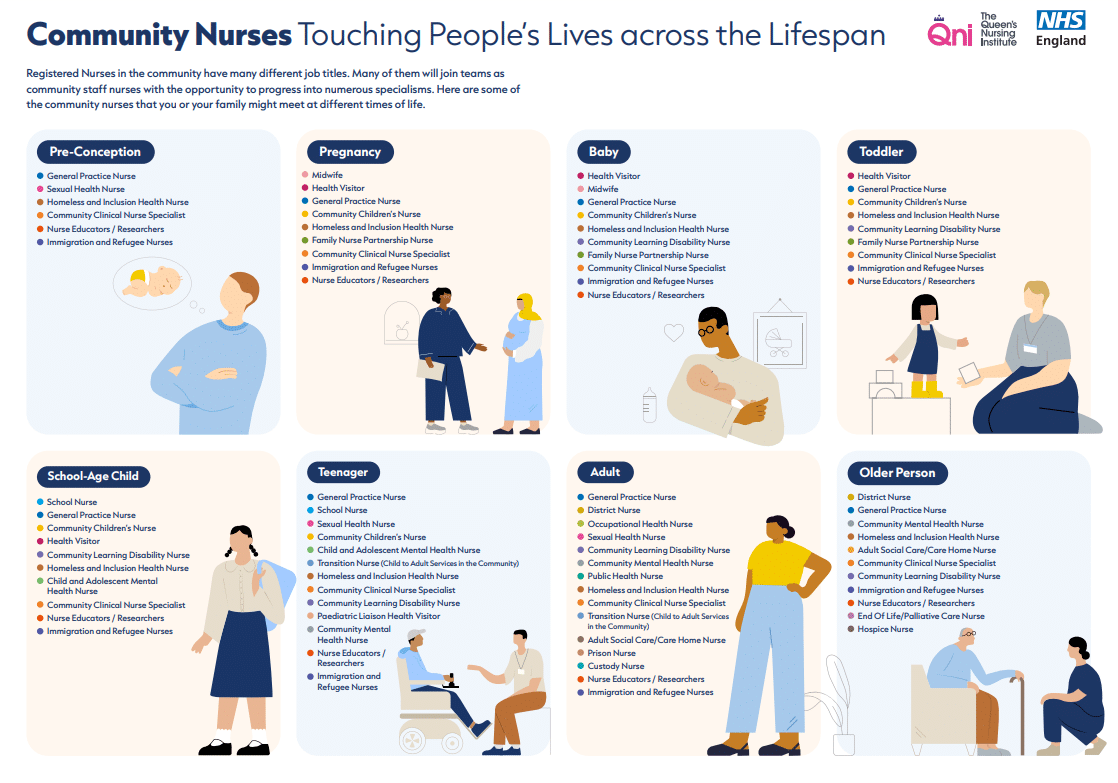

When I say I’m a nurse, I often get asked “Which hospital do you work at?” Yet, we will all encounter a nurse or healthcare worker based in the community throughout our lives:

I would particularly like to highlight those nurses and services working in more hidden places and with marginalised groups. This includes nurses working in the prison service, in hostels for people experiencing homelessness, with asylum seekers, and nurses doing street outreach with people with people at times of real distress.

Nurses based in the community are the eyes and ears of the people they serve. Unsurprisingly, their decrease in numbers correlates with an increase in health concerns. The Institute of Health Visiting’s 2023 report highlights that since 2015, over 40% of the Health Visiting workforce has been cut. Consequently, Health Visiting teams have been prioritising child protection and child in need cases, limiting their ability to conduct preventative and early intervention work. The Health Visitors interviewed for the report shared concerns over an increase in the number of children with developmental difficulties, the rise in babies and children referred for safeguarding concerns, and the number of families struggling due to the cost-of-living crisis. Could a shrinking workforce be missing opportunities to detect issues early on?

In the adult population too, nurses engage with marginalised people who can be unaware of their healthcare rights or disengaged altogether, due to access difficulties or negative experiences, something we’ve all experienced to a degree as well. Well-planned community care teams can prevent hospital readmissions or inappropriate A&E visits. However, a stretched service ends up operating in a reactive way, missing vulnerabilities, and leading to more A&E visits.

We can keep carrying out serious case reviews, root cause analyses, commissioning reports and research to investigate the causes. However, we already know what the problem is; our healthcare services are understaffed and underinvested. To provide more localised care, the scales must be tipped so that community services are properly valued for their roles, and capable of carrying them out safely.

By investing in preventative healthcare, early intervention services, and health promotion at its basic level, we can:

- ensure that our communities feel confident in recognising concerns early on

- make healthcare workers visible and accessible in the places that people use the most

- support healthy behaviours for a healthier society

Despite an increase in health needs, greater demand on GP services, and repeated government promises, investment in community health services just isn’t growing. The Office for National Statistics publish yearly UK healthcare expenditure figures. Around 8.2% of the total UK healthcare expenditure in 2022-2023 went to preventative care. This was divided between immunisation programmes, early detection screening services, surveillance, and information. However, prevention is much more than this; it’s supporting people to take care of themselves, to prevent disease in the first place.

My 11 years working in community health care services has been marked by the erosion of grassroots health promotion. The kind where I would go to day centres, church halls, Healthy Start centres, and schools to talk about all sorts of topics with parents, students and the general public. Instead, we’ve seen the appearance of more and more managerial or clinic-based roles. Long-term funding for grassroots work just isn’t available.

Spending on early health promotion and care in the community makes financial and common sense. Particularly given the increase in chronic health conditions, mental health needs, and our ageing population, investing in health upstream will save expensive hospital visits and support people to live healthier lives in their communities. After all, most of us are more likely to meet healthcare workers in community settings rather than hospitals.

Lord Darzi’s report does a great job of highlighting this issue, but investment in community healthcare services has long been a fixture on government promises. The next few years will show if this call to action will be brought to reality.

Kirit Sehmbi

Homeless and Inclusion Health Project Lead

References:

Gorham and Wood (2023) Unlocking the power of health beyond the hospital: supporting communities to prosper.

Office for National Statistics (2024) Healthcare expenditure, UK Health Accounts: 2022-2023

The Institute of Health Visiting (2024) State of Health Visiting, UK Survey Report.

Back to Blog

Back to Blog